IPF webinar on "Skill India: The Future Roadmap"

Total Views |

IPF webinar on

"Skill India: The Future Roadmap"

June 18, 2022

Speakers:

Dr. S. S. Mantha

(Former Chairman, AICTE)

Dr. Manish Kumar

(Former MD and CEO, NSDC)

Moderator:

Dr Kuldeep Ratnoo

(Director, India Policy Foundation)

Dr Kuldeep Ratnoo:

I welcome you all in today’s webinar on Skill India: The Future Roadmap. We are very lucky to have two eminent academicians and bureaucrats who have held very critical and very important positions in our country. Our first speaker today is Prof S S Mantha and the second speaker is Dr Manish Kumar.

Prof Mantha is former Chairman of All India Council for Technical Education. He is an engineer by education. He did his B. Tech. in Mechanical Engineering from M. S. University, Baroda. Then, he did his M. Tech. from VJTI, Mumbai and he did his PhD in Combustion Modelling from University of Mumbai. He has held various positions in academics. He was also President of the National Board of Accreditation and Deputy Vice-Chancellor of SNDT Women’s University, Mumbai. Currently he is serving as Adjunct Professor in National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore. He has been awarded honorary doctorates by VT University, Karnataka and by DY Patil University, Maharashtra.

Mantha ji is a prolific speaker and writer. He frequently writes on issues concerning technology, education etc. He has also been educating people by uploading videos about blockchain technology and other subjects. We are indeed lucky to have him here. He has written a lot about Skill India. In fact, the curriculum framework which was prepared long back, he had made a major contribution in that. Recently, he wrote a paper for India Policy Foundation on Skill India. We are very lucky to have you here sir. We look forward to hearing you.

Our second speaker is Dr Manish Kumar. He comes from Indian Administrative Services. He worked as Secretary in Government of Tripura. Later on, he worked as Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer of National Skill Development Council. In between, on deputation, he has worked with UNICEF and World Bank. Currently, he is associated with World Bank as a senior consultant. It is a pleasure to have you here sir. Manish Kumar-ji also comes from engineering background. He did his B. Tech. in Mining from IIT Dhanbad. Later on, he did his MPA from Harvard Kennedy School. He did his PhD in Institutional and Regulatory Economics of Public-Private Partnerships from George Washington University.

Today, we have two storehouses of knowledge and experience. I am looking forward to hearing both of you. We are lucky to have eminent audience also. I welcome you all.

Dr. S. S. Mantha

Good evening to you all.

I will take you through what Skill India Mission is all about and the concerns that are there in the implementation part of it. Maybe, suggest a few ideas for you all to think over and implement for much better outcomes. What I will do is to show you a small presentation.

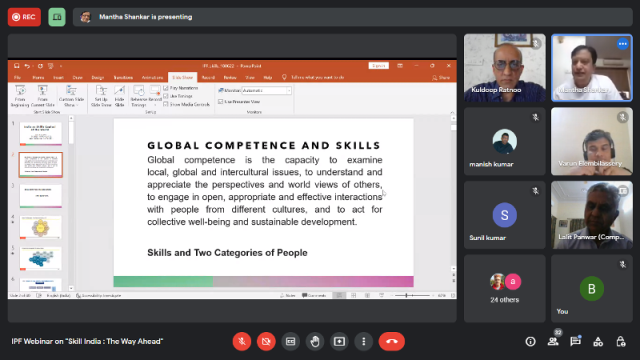

Without going into too many details, we all understand what global competence and skills are. Whenever we talk about skills, it is the competency-based skills. So, there is a certain training that is given for a certain competence in a sector and we build skills for that competence. Fundamentally, we need skills for two categories of people. One is the skills required for those who are going to college. Since our Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) is about 26 today, I will call that 25:75 syndrome which means 25 per cent are in colleges and the rest are probably drop outs or may not have gone to colleges or schools. Now, whatever skills mission we implement, it must be applicable to both the groups. The skill set required will be different but the recognition must be made of the fact that both the groups need skills.

First of all, I am looking at skills for those who are going to colleges. And in that space, we talk about employability skills and additional skills which some of the institutions are able to teach. Some of the regulatory mechanisms that have been put in place are allowing people to do it. But still, there is a certain gap which needs to be bridged. For that, we need to look at how the industry is transforming. We all understand the new industry which is complete automation. A day will come when machines will talk to machines. In the earlier days, people used to talk to machines for programming and things like that. In times to come, complete automation and artificial intelligence will take over in every single area. Therefore, the students who are trained today needs skills in autonomous robots, simulation, system integration, IoT, cybersecurity and things like that. So, some of the institutions are providing additional skill sets for these people to be trained through certification programs which are offered by third party providers and sometimes through experts in the institutions and so on. This is one area which needs a little closer attention. This is also needed because it affects the entire value chain in an industry. The value chain extends from engineering design to one end to human resources on the other. It affects every single part of the value chain. Therefore, the students who are in the technical colleges and even in the science colleges who would get into support services, they also need skills in many of the areas as it affects every part of the value chain.

We all understand that today there are several sensors around, there is Internet of Things (IoT). Anything that communicates is a thing. IoT on one side and product innovation, process innovation, autonomous agents and digital networking on the other side which forms Industry 4.0. Between these two, we have what we call Labour 4.0. Therefore, our engineers whom we create out of our colleges need to fill this gap of providing that Labour 4.o. So, they need training in digitised services, in Industry 4.0, in smart factories, smart products and things like that.

In terms of soft skills that we talk about, there are several skills that were listed in 2020 which several people have talked about. But one specific skill in this, I would like to mention is the cognitive flexibility. Today, increasingly, students will require to fit into different spaces which means they come with a certain set of skills. But on the job, they acquire additional skills and are able to fit into those challenging job sectors in other areas which would be available. This means cognitive flexibility or the ability to adjust in different environments is a very important skill that they require.

Now, if I look at the entire world employment sectors, there are seven sectors in which we can divide the entire employment scene. For example, it can be engineering, it can be data science, it can be product finance marketing and management etc. These are the seven verticals (refer to the ppt) in which jobs are available predominantly today, whether it is the primary employment sector or the secondary or the tertiary employment sector.

There is an essential skills map for industry transformation which the industry leaders mention. There are three skills which everyone who goes to college should acquire, essentially in the domain of science and technology. These are business skills, technical skills or technology-based skills and data skills. For example, if somebody wants to make a career in finance, he would obviously require mathematical finance, financial modelling, financial engineering as business skills. For technical skills, he would require Microsoft Excel, algorithmic trading and so on. Out of data skills, he would require forecasting etc. Unfortunately, what is happening is that our colleges do not get into these areas at all. Therefore, there is a certain gap that exists when somebody would want to fit into a certain employment space.

Coming to future jobs, I would like to point out one aspect. In the earlier days, we had a pyramid like structure for employment where we used to have entry level jobs more in number and as you go up, the skill level goes up and the numbers come down. But today, it is no longer so because of the introduction of a lot of automation, artificial intelligence and artificial agents as we call. They have actually automated the entry level jobs which means that the base of the pyramid is shrinking. Therefore, we need higher order skills even at the entry level but reduced in number and as we go up, the pyramid actually becomes like a pipe-like structure.

During the last two years, there is a lesson that we have to learn. The low skill jobs were the hardest hit by Covid-19. Therefore, we need to relook as to what skills are required for a Bachelor’s degree job, what skills are required for a professional etc. We need to understand this entire space of employment versus skills that we have. So, collaboration, communication, critical thinking and creativity are the other skills that we would require. The National Education Policy (NEP) talks about multi-disciplinary research and so on. But we cannot do multi-disciplinary research just because we desire it. There are certain building blocks that are required which have to come in place and everything builds on an approach to building skills for the future of work. So, hands on learning, there is a core that is required, there is a multi-disciplinary approach that is required. And then from hands on learning to core to multi-disciplinary, you build a career. That is how the skills work.

There are different career paths available today based on the skills we develop. Guided project is a concept that has come in. So, in the engineering colleges, there are several third-party providers like Coursera, Udemy, EdX etc. They all get into this area of guided projects, provide internships and so on.

Within the area of agriculture, there are several opportunities if the students are to be future ready. There are undergraduate agriculture-based studies, there are courses available to upgrade those skills and that is something that the employment sector recommends today. These are the possible career paths for agricultural students today. There is precision agriculture, supply chain technology, crop quality management transparency, visibility across supply chains. There are lot of areas where agriculture is seamlessly getting into the use and application of technology. And that is where new jobs are being created.

We have also seen one of the Google announcements where Google career certificates are being talked about. They actually say that there are no degrees or diplomas required but a set of skill sets are required to get into an employment sector. This is how they define a pathway to jobs. There are in demand, they have high paying jobs and so on. The entire segment is seen in terms of the actual skill sets that are required.

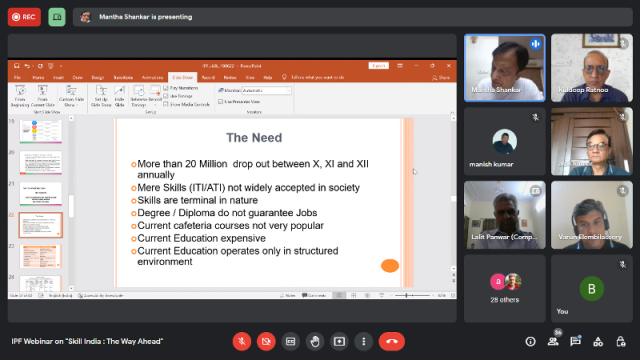

What I have talked about till now is those who go to colleges where the ratio is 25:100. Now, there is a large number outside that space which is the 75 per cent Syndrome. In that, there are essentially two cases. One case is where they need skills but they would also like to pursue school/college studies. They may be drop-outs or they may have gone out for some time. They want to come back to the education system. But they are essentially interested in employment for their own well-being. In order to meet that employment, they also have another goal of someday completing the graduation or diploma. The second case in the 75 per cent Syndrome is those persons who are not interested in any education per se but they are interested in skills which will allow them to be small-time entrepreneurs or maybe get an appropriate employment. So, what ITIs and ATIs do is to build advanced skills which are trade-based. For example, somebody is made an electrician or plumber. These are trade-based skill sets and they will only allow a certain job. Those skills are terminal in nature which means they do not have any future on that. Therefore, the acceptance within the students is very less for these kinds of courses. In a generic term, we say that vocational education is no more looked at favourably by the students.

Another point is that degrees and diplomas are not guaranteeing jobs today. UGC actually has a cafeteria-based courses which were popular at one time but later on, it went into a question mark. What was happening was that along with a degree, whether it is B.Sc. or B.Com., students were allowed to take two additional skill based courses. Now the problem is these additional skill-based courses were available in a menu kind of thing. Therefore, it is called cafeteria-based courses from which the students can choose skill courses. Now, this was not very popular for over a period of time. One reason was that students were selecting courses whatever interested them, not necessarily connecting them to the employment sector. Second is that the institutions which were offering these kinds of skill-based courses were purely looking at it as a business model. If there is some money in it, then they will get trainers and infrastructure for these courses. If there is no money, they won’t do it. In effect, the choices get shortened and the menu for students was less. In fact, similar things were happening with B.Sc. vocational which was a very good initiative for building skills and education together. Current education is expensive and it operates in a structured environment. But the NEP has addressed this to some extent, in the sense that students are now allowed to drop out after first year, second year, third year and fourth year.

The challenge here is how do we create the curriculum which actually connects him to an appropriate job when he chooses to drop out? Therefore, it is necessary that the employment scene is mapped to the kind of education system that we would probably have in the future and build competency-based skills for a certain job role that is available. Otherwise, what will happen is people would end up continuing all the four years, getting a complete degree and it is business as usual. But if you really want to visualise the kind of flexibility that is available within NEP, a lot more needs to be done in terms of mapping it to the exact industry requirements and creating content accordingly.

As we know, there are several vocational sectors, some of which are accepted worldwide. For the first group of the 75 per cent Syndrome, NSQF as we all know has several certifications and there is an equivalence created here. There are vocational qualification certifying bodies. For example, you have levels of study that starts from Class VIII, IX and it goes forward. Every time, you raise in the certification level, you get higher order skills and by seamlessly building into the current educational system, one can realise both aspects of skilling as well as providing the student a degree or diploma, if he so wishes. But the flexibility is always there for him to get out of any certification level and come out for an appropriate job at that level. In fact, the Agnipath scheme that has been announced would require something like this and implementation of that will be extremely important.

Typically, the vocational framework that we were proposing was that every certification level should have certain skill hours and certain education hours. As the level increases, the skill level goes up and the educational level goes down. This means that the person will acquire more and more skills as he goes in the higher level and become better employable. Therefore, the education part in the initial years is kept almost similar to what is happening in a conventional school. That is because the chances of his wanting to go into the professional stream or getting into the current educational system and coming out of the educational system if he so wishes, all those flexibility features are built into this. It is a win-win for everybody in terms of progress and in terms of acquiring skills.

One important point that I wanted to highlight here is that there is a Carnegie Mellon credit-based system which defines the extent of study in a classroom and the level of skills that one acquires. What it means is, if in a classroom, if I study for one hour, I get one credit. That is face to face learning. If I go to a lab and learn for two hours, I get one credit. That is a workshop part or a lab part which is the hands-on part. This is the general Carnegie Mellon way of defining credit. But the challenge is really in defining credit for skills. For example, if I get four hours of skill training in an automobile workshop for engine maintenance, then I get only two credits. As opposed to this, in a different sector, for example beauty and wellness, if some of the courses are taught for four hours, will the credit be the same? Those kinds of questions are also answered here in the 3-4 slides (refer ppt). It gets all the sectors into one frame of reference and it accounts for the level of difficulty within the sector at resultant levels. This is extremely important if one wants to provide a degree and diploma and say that in the professional world, this degree from a vocational system is as good as the degree from a conventional system.

As I said, there must be multiple pathways available. Some flexibility must be available from one system to another. Today, there should not be a problem for anybody to get into any system with requisite skills. Therefore, the student should not have any misgiving about getting into the vocational system and believe that he would lose something if he did so. This shows all the available pathways that are there. That was about the 75 Syndrome and Case I where I talked about students who would want skills but they may also want to pursue a degree or diploma as they go along, studying at their pace and acquiring skills at their pace.

Now the second part of that 75 Syndrome are students who want only skills for employment. They are not really interested in acquiring a degree or diploma. These are people who would have dropped out and probably worked in a garage for 10-15 years and acquired some skills. How do we recognise their prior learning skills? One important feature that we must understand here is the need for grouping of skills for employment and the need of certain basic level of understanding of certain aspects of leading a life. For example, I need communication skills, not the entire grammar or things like that but I should be able to communicate in maybe English or a local language. This also talks about providing some basic communication skills, some basic things to understand the nature, to understand the computer, basic accounting etc. Then presentation skills, grooming skills and so on. We are also suggesting one additional language besides the local language or his mother tongue. That increases the mobility between states. That additional language can be a foreign language as well if the student chooses to go out. We don’t need any brick-and-mortar things to do this. We need an existing college or framework. The only idea is that they should follow NSQF in letter and spirit.

Now, I will just give you a potential which will tell you how powerful this entire Skill Mission can be. We have almost 1.5-1-6 million schools in the country, 40,000 colleges, 10,000 ITIs and we all know that most of them do not conduct any classes after 5 p.m. Infrastructure that is there is lying waste. I am not saying that every institution does that but most of them do not do anything after 5 p.m. These could be used to conduct programmes after 5 p.m. or on Saturdays and Sundays. Assuming if we create one division of one hundred students in each college, ITIs etc., in any sector and any specialisation that is defined by the local conditions, then as you know only 10 per cent of the above facilities are used, then you can train 20 lakh students every year. In order to do this, financial scholarship models may be created. You have Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana and other things which can be suitably amended to fit into these requirements.

Today, there are many skill centres, there are trainers available, there is infrastructure created but somewhere there is some connect that is missing. Attaching them to the current universities is not the solution. They are autonomous, they have other jobs to do, they are more interested in conducting UG/PG programmes, research and so on. Therefore, burdening them with skill education may not be the right way to look at it. There are many skill bodies but the implementation would always be a problem area. Too many bodies in centre and states lead to disaggregation. There is something that the centre is saying and the state is actually implementing. Therefore, there is always a conflict there. So, developing training centre supply chains in sectors across is extremely important. If you look in Germany or France, there are training centre supply chains. Why can’t we create that? In automobile sector, pharmacy, textile sector etc. you find them. Creating, enabling and facilitating regulatory environment is necessary. For example, suppose we create a National Skill University and we create regional centres in every district or finer than that, all these can use the standards and policies set by the central body and then they can implement them and the students can approach the district centres. The certification can be authorised to be given by the regional centres by the Central body. It can be a very good scheme to bring everybody in the space under one umbrella. The ultimate idea should also be to promote the Make in India concept. We need a blueprint for Make in India which connects these skills that we are talking about. Such a university can also do a lot of research in areas which are forgotten today. There are several skill sectors which can provide a lot of opportunity today but they are not doing it because there is no ecosystem that is available. So, the university can get into that area and then develop technology enhancing curriculum. They can conduct trainer programs, develop accreditation method for trainers and trainees. We can participate within the Sydney and Dublin accords where the mobility increases. People who are trained here can get into other countries. Then revenue models for sustainability needs to be there. Collaborate with American Association for community colleges. Collaborate with industry bodies for placement. We need to create a corpus with central, state and CSR funds. We need to create soft loans to fund scholarships and so on. Finally, we need to conduct skill melas in different cities. Something on those lines is already happening. We need to audit the current events that are happening and see how they can be optimised to reach almost everyone in the spirit in which NSQF was designed. In the skill mela, schools can be represented, colleges can be represented, trainers can be represented. In another sector, bankers, NGOs, CSR initiatives can be integrated.

In the fourth sector, we actually seek students out from active participation and from nearby communities and other persons interested in acquiring skills. They can do spot registration or online registration there. So, there will be some central podium for dissemination of information. In this process, we create the labour management integration system which is extremely important for a country like India. There can always be a blitz on skill media. Some collaborations will be required to do all this. That is my take on the Skills Mission. There are a lot of things that can be done and that can be spoken about. Based on the questions you have; I will come back to it again. Thank you so much for the opportunity.

Dr Kuldeep Ratnoo:

Thank you, Prof Mantha ji. You elaborated on how academics and skill training can be put together, can be merged and can be utilised efficiently for training our youth. Particularly in terms of matching career and opportunities in the industry where not only our college students but students who are out of higher education system, even school dropouts, they can be trained, they can be educated for the future challenges. So, thank you very much sir for giving us insights and for the very detailed presentation, particularly from academic point of view and also from curriculum point of view. We are very happy and excited to hear you. We will come back to you when the question answer session starts.

Now I would request Dr Manish Kumar ji who worked as Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer of National Skill Development Council (NSDC). He comes from bureaucratic background and he headed the Council which was looking after the entire Skill India mechanism. Now, moving from academic to implementation part, over to you Manish Kumar-ji. Please provide us your insights and your guidance.

Dr. Manish Kumar:

Thank you very much for inviting me. It is a great pleasure to listen to Dr Mantha. I think he provided a lot of insights on what we can do to improve and strengthen the skill initiative that is currently underway. I will put in a few points in addition to what Dr Mantha has already spoken. The points which I will make will be firstly, very global level view of what is really happening to the whole education system as well as the need for skilling that is emerging and how that is so relevant for India. It will be very macro level like an aeroplane view. Secondly, looking at our challenges because I think India is not a regular kind of country. We are both a country and a sub-continent. We are a civilisation. We are far more complex to manage than many other countries which are so much smaller that could be the size of our states. I think our population which is 1.4 billion is equal to the population of all the 40 countries in African continent. That is the challenge which you have. So, I will talk a bit about the challenge and finally about the approaches. In the approaches, already Dr Mantha has covered quite a bit and I am in sync with all of them in terms of how we should take up stuff. But I will have some ideas with reference to the practical realities of how you should be looking at skilling at different levels.

Firstly, looking at education, I think in the traditional method, when our education system was developed, it was more at the time of Industry 2.0 and it was assumed that education will provide the broad backdrop that was necessary, the framework that was necessary and skills should be acquired on the job. As people go into jobs, they will learn new skills, they will get more skilled and they go on to new jobs. So, education system was almost like a factory line that you have Class I, II, III, IV etc. It is almost the same line that you have in a car factory.

So, this is Industry 2.0 and also Education 2.0 in some ways. With the coming of digital revolution, that is the coming of the internet in 1990s, things changed and the manner in which the industry itself is evolving has in a way gone through massive changes. Because of that the educational system that we are relying on, there is bit of gap on how education eventually converts into skills. And is it too expensive? When I talked to some professors in MIT education lab, they raised exactly the same questions saying that the expensive education of many of the U.S. universities doesn’t lead to skills that are actually relevant for the job market. And those skills which are relevant for the job market are available much more cheaply are not provided by the universities. There is kind of gap between the two. They were talking about how you could in a way remodel the education system that will become much more modular.

As Dr Mantha pointed out, you can keep on acquiring skills but you are not forced to complete a full four-year course only because degree says that is needed. Therefore, you are making lot of expense because of that. I guess the changing paradigm in the world, with the coming of internet, the world of digitisation has become part of us. It is still in infancy and often it called life transforming technology, as we know. With that being at infancy and still changing so rapidly, the educational system needs a revamp. The New Education Policy actually addresses most of these issues and we are lucky that we are moving in the right direction overall.

Coming to the second part of this and I am now looking for the industry perspective. There is a very interesting trend that we need to keep in the back of our minds when we talk about skills. This also will highlight how important the role of government is when it comes to skills. If you look at data from 1920 till today, pick any of the major countries in the world, the rate of return to capital and the rate of return to labour, you will find that both of them were more or less moving steadily upwards but almost in sync. If there is a graph, then the rate of return to capital will be slightly higher but almost in the same trajectory would be the rate of return to labour.

This continued up to 1990, the time when the life transforming technology of the internet came in. Then, there is a sudden change in the curve. What is happening after that is that the rate of return to labour has flattened and rate of return to capital has shot upward. Essentially meaning, if you think of Facebook or if you think of Elon Musk, you realise how technology is leading to huge wealth to companies. Whereas on the other hand, the labour because of the rate of return being higher would get some benefits. So, every time, an investor puts in some money, there is extra money that is generated because of the skills that the labour had. So, there was a sharing that occurred. There was an increase in real wages of the labour and this continued. The labour kept on improving the skills and the rate of capital also kept on increasing. That is the trend up to 1990s. After that, it is all technology driven, it is all internet driven, it is all digital driven.

The unfortunate part is that this change in technology has been very quick and has not stabilised yet. As I said, it is still in infancy. Therefore, every time an investor ends up making money, they are putting in more and more back into technology, not sharing with the labour. There is almost a flat real return of labour and that is a matter of concern globally for many of the economies. That is the trend which is there. Now when we talk about skills, we realise that the private sector is unable to do as much as we did in the past. The government has to step in. Whenever, there is market failure, it becomes the government’s responsibility. And that is exactly what the government of India has been doing as we notice. This is the broad global trend which I am talking about.

Now looking at challenges. I already mentioned about India being both a country and a subcontinent. So, how should we think? Dr Mantha said it beautifully. We need to think a little more granular. We need to go down in our perception of how skills should be attached. Everything being done at the national level; it is good from a technical perspective that you build technical capacity. But the real implementation and the real assessment of what is needed has to be very local. I am coming to that. I will put a few numbers that will help you get a sense of how challenging our situation might be. If you look at our total workforce, these are only approximate numbers and are slightly dated but more or less in terms of magnitude, what I want to express. Our total workforce would be about 41.5 crore of which about 38 crore are actually employed. There would be about three crore who are not employed, of which half of them are students who are looking for jobs. That is how we are as a country. I think what we need to understand is of this 37-38 crore who are employed, 80 per cent of them are informal labour. They are basically people who may not have formal degrees in their hands of what they are doing but interestingly, they are paid by the industry for the work that they are doing. Which essentially implies that they are adding value to the economy.

I will come to some numbers of how much people are earning in different quartiles in terms of income. 20 per cent of them in the 38 crore are formal. We might call them as having diplomas or degrees from colleges and even ITIs. But 80 per cent of them don’t. That is the complexity of our problem and it is the problem that we have to solve. Now looking at the income bracket itself because that gives us a sense what is the nature of the people whose problem we are going to change. If you look at our 41.5 crore labour force, the lowest income quartile, the first 25 per cent of the labour force, they earn Rs 26,000 or less. The next income quartile we have earn between Rs 26,000 to Rs 37,000 per month. The next quartile earns between Rs 37,000 to Rs 57,000 per month. That is the composition. Anybody who earns above Rs 57,000 per month in India is the top 25 per cent of India’s labour force. Anybody who earns more than Rs 88,000 is top 10 per cent of India’s labour force. This also gives the paying capacity of people who earn and how desperate they might be for jobs and therefore, their ability or inability to either spare time for getting skilled or getting educated and the need for short term courses. As Dr Mantha said, if there is a credit system so that even if they spend two months this year, two months next year and two months, next to next year, they all could be still stitched together rather than asking the person to spend one chunk of six months because the income ability of that person may not provide him that opportunity or luxury of spending so much time together. I think keeping that awareness is very important from a policy perspective.

Coming to some of the approaches that we could take. Firstly, when we talk of skills, we have to reflect that people can have different visions about why skill is necessary. Therefore, this is often contested that it is important for an individual to be skilled as that is how a person’s life will become better. Or should it be economic centric? That we want to skill because we want to increase the GDP of the country? This is a very important distinction because sometimes when you put money into economic productivity, it may not lead to welfare of everybody. It may lead to increase in GDP but it is a question of resource division. Eventually, it comes down to resource division and that is the job of public policy. Now should you be putting money into things where everybody gets employment and there is more likelihood of employment to everybody or should you put money where people necessarily are trained in a way that the GDP of the country grows and you don’t care how many people get employed. You will find a bit of contestation on this idea. Therefore, sometimes people hold very strong views on what should be the role of skilling and how should it be delivered? In my view and generally speaking, including some of the surveys done in World Economic Forum, I had found that the human centric approach is what some people feel most comfortable with. They feel that there is a need to keep human beings at the centre of any thought or efforts in skilling. GDP does matter and yes, it should be a consequence of whatever skilling you do. But it should not be the starting point. You need everybody to have equal opportunity. So, there will always be the equity versus efficiency argument.

I think whenever you have a human centric approach, then the role of government becomes very important. Therefore, among some of the things which are necessary, one is to make skills more aspirational and that is not an easy job. It is a tougher job. One of the issues that the NEP wants to address is bringing skills at school level. The conversation about skills happening at school level is a very important element of the NEP and there is a lot of detailed thought process that is underway which I believe will be rolled out in maybe a few months’ time.

The second thing I feel which is very critical and this is for the government again, is to look at the human centric need for skills in different parts of the country in a much more granular way instead of having a very top-down kind of approach. It is very convenient for bureaucracy very honestly because you are able to account for money, you are able to track it through a computer etc. But what might be needed in a place like Gandacherra which is in the remote part of Tripura is not the same as what might be needed in Palakkad in Kerala.

The interesting thing is we have enough data with us to know what are the important human resource position at district level. We would actually know how many people are unemployed at the district level, at what age group etc. We have enough information about the national level as well as the state level that what are the main industries, what are the main occupation of people, what are the main belief system of the people etc. I think the need is the main criteria. The skilling plans are very granular that you have to think district and perhaps even lower. You have to make it deeper. It doesn’t mean that we don’t make state level plan or we don’t make central level plan. We do that too.

Having very deep district level plan is critical because as I said, that plan is for people who are at Rs 26,000 and less or many times even Rs 37,000 or less. The central level plan would mostly be for people who are Rs 88,000 and above because it is easier that way. The lower you go, the closer it gets to people and therefore, it gets more people oriented. So, it is likely that it touches the lives of people in a stronger way that if it is made at the central level. Therefore, the need for using data and the need for using district level, state level and national level plan. The district should have increased capacity and should be focused on all the things that Dr Mantha said. There is so much infrastructure already available and so much capacity. There would be a need for hiring technical capacity at the district level on which the focus should be to ensure enough infrastructure and equipment. That is where the planning should be at the national level and the state level but more and more of actual action should be at the district level. This is one thing I strongly believe in.

Another thing which is very important given the number which I said, the 80 per cent of the 38 crore who are in labour force being already paid by the private sector for the work that they do and one crore people being added every year to the labour force. Of these 38 crore who are already employed, who don’t have a certification, they are informal; the RPL (Recognition of Prior Learning) is very important. We have an RPL programme in our country. It is not the most ideal but still it is very effective in the field. Just to give you an example, Jaipur Rugs, a company which supplies carpets to many of the hotels in United States and many other countries also, they conducted RPL in remote parts of Rajasthan where women who were involved in making parts of the rugs. I visited them and asked what is it that they gain? Does it really lead to any benefits? I realised something. Many of these women are working for 20 years. They said that through the RPL process, for the first time they came to know what really happens to their product. They said that they make just a part of it and they give it to the agent and they are given money. They never realised that it goes so far away. What they said is, “We feel great pride in our work, we never realised that how much value addition we do to the country and the welfare that it brings.”

Pride is a critical part of anybody who is working. First level change was that pride. Second, at least half of the 20 women I interacted with said that they never ever attended a single class in their lifetime. This was the first time that they attended one in their lifetime. They also got the certificate, which was another first for them. We often don’t appreciate how much difference this small stuff can make in the lives of people. But part of the job of any skill development is to bring that joy of work. The aspirational value and the belief that what they are doing is good and great and that they have been contributing to the larger society’s welfare. So, RPL brings that in a massive way and is a very important tool that should be used in a much larger way because the number of people who need RPL is huge. If you look at 80 per cent of 38 crore, that is a massive number. There is a need for doing far much more than what we are doing now.

This effectively means that one of the fundamental things about skill is that it is not so much about how you are teaching, it is about assessment. That you have a global system of assessment. We should be focussing at how good is our assessment system and how fool proof is our assessment system either through universities or any institution that we build up. If assessments are good, then you are giving a signal to the market that whoever gets filtered through my assessment is somebody of high quality regardless of how many hours that person might have worked or not worked. Each of us pick up things based on our own intrinsic capacity, some of them take 10 hours to learn a job and some of them might do it in two hours. As long as you clear the assessment with the same marks, it means that you are equal when it comes to skills.

I think the whole aspect of assessment and how this assessment should be done, we have to establish certain protocols. We need to work much more deeply and make it more robust. I feel sometimes that instead of spending our time on training centres which is also necessary, we should spend equal time in assessment because that is the filter through which you can say with conviction that whatever is coming out is going to be useful.

Another part is essentially looking at the self-employment potential. Many of the trades or the many of the service sector occupations have potential for self-employment. How do you link it to bank loans and how do you link it to some way of people getting into doing their own businesses? It is something that we need to reflect on.

Finally, when it comes to the private sector, they should have a more economy centric approach. There are centres for excellence which the private sector has been doing. For example, L&T has made a huge centre for excellence in Mumbai. We require more of such in every city and town which are focussed towards industry but is also a kind of standard bearer of what might the best thing in a particular situation may look like. I think at the back of our heads we should always keep in mind that the requirement of rural and urban India is going to be very different. The rural India will become very dependent on government whereas urban could do with both government and private intervention.

Therefore, focus of government should be about more deeply thinking about rural. One of the big chunks that we forget is agriculture and the fact that there are churnings that are happening. A lot of people from agriculture are moving into new trade. For example, the food delivery boys in Bengaluru come from agricultural background and the interesting thing about them is while they earn a lot of money, some of them almost earn about Rs 70,000 per month but they work only four months. When we asked them why do you work only four months, they said that because we are used to working so much in agriculture. So, sometimes it is not just about the work, it is about the culture, it is the previous profession that the person must have been practising. Therefore, the need for the soft skill part which Dr Mantha spoke about becoming important. As we skill people, then let them know about how culture is different in agriculture and how the new culture in a delivery job is going to be different and will require a different approach. Weaving all of these together is something which we will have to reflect on. Making things much more granular and taking it down to district and maybe the block level is what we have to reflect on. These were few thoughts which I had to share with you. Thank you so much!

Dr Kuldeep Ratnoo:

Thank you, Manish Kumar ji. Thanks a lot for giving us insights into the large demography that we have, as you mentioned earning below Rs 26,000. You also mentioned about the workforce we have and the challenges not only in terms of implementation and the challenges for rural and urban population, their requirements and the crisis which we have been facing. Also, you talked about the cultural differences which we have that are also affecting the inclination for job as well as the kind of training one needs to look for. Before starting the Q&A session, I would request if anybody wants to make any comments. Lalit Panwar-ji, would you like to make any comments as you have headed a Skill University in Jaipur?

Lalit Panwar:

Thank you, Kuldeep ji, Dr Mantha Saab and Manish Kumar ji. It was a very interesting presentation for me. I kept on taking notes and it was a good learning for all of us. Only two things I would like to flag. The first and the very important one is how to make skill education aspirational? That is a very big issue for all of us. We want good plumbers but we don’t want our sons and daughters to be plumbers or go to plumbing schools. Second is that students who are pass outs with just a B.A., B.Com. degree, their employability is almost nil in the market. So, why don’t we introduce skills into their curriculum which are employable and are in demand in market? For example, a commerce graduate in second or third year can do a course on GST Tally. A B.A. student can do something on event management. A B.Sc. student can do something on IoT. Such short-term courses can make students employable. These are the two points I wanted to make. Thank you.

Dr Mantha:

Making skills aspirational is extremely important. But the larger question is how do we make it aspirational? Everything is possibly linked to the employment sector at some point of time. We certainly need skills to grow as a human being. Somewhere along the line, probably we also want to learn so that we are productive enough and can look after ourselves and our families.

The problem is aspirational and must be looked at from an employment perspective and in that sense, we have a primary employment sector. World over, it gives you employment opportunities about 10-15 per cent. It depends on the produce from the earth which means mining, agriculture and so on. Though we say, agriculture gives 50 per cent employment and more than that, it is only seasonal. Therefore, there is no sustained employment that is available in that sector.

The secondary sector is essentially the manufacturing sector, unless it grows at maybe 30-40 per cent which has been stagnant at about 16-17 per cent in the country, that cannot produce jobs which are productive enough and the secondary sector has the potential to create about 35 per cent of the employment opportunities.

What remains is the tertiary sector and that is the service sector. There are almost 50-55 per cent job opportunities possible there. Therefore, everybody gets into that space. Even those who are otherwise qualified to be in the secondary sector would probably migrate to the tertiary sector because there is a job available there. But this doesn’t look at the aspirational value even in that space. So, what one needs to do is look at the industry as to how that is evolving, map the available job roles. It is a difficult job but there is some possibility of doing. It is done in some sectors but it is not done in every sector. But if something like that is done, then you can connect training to the actual employment potential.

Therefore, one can move people away from the aspirational value that centred around acquiring a degree. If it is also positioned around getting a decent employment, that also will raise the aspirational value. Having said all of this, there must be a conscious effort to create new employment markets. Over a period of time, the technology changes and the available employment market gets saturated. Therefore, one needs to constantly create new employment markets and be innovative in that space. All that put together can probably address the aspirational value and it is a very important aspect.

Sanjay Ganjoo: I would like to make some observations based on working in this sector in the last 12 years. The first point I would like to put across is while the educational system in India is getting institutionalised, consolidated and centralised. For example, you have IIT-JEE, NEET, Central Universities entrance test, in those educational sectors which have matured to a large extent because those who appear for IIT, NEET etc. have some sort of maturity. They have at least gone through a process of studying up to class XII but still we find that there are institutional faults and there are faults within the students. So, we have institutionalised this and the cream comes to these institutions which have been created at the central level.

But unfortunately, in the skill space which to a large extent is raw, immature, informal in character, we have tried to deinstitutionalise it, we have decentralised it by creating the sector skill council and many such institutions for assessment. Even for imparting training, we are day by day creating new IITs, new IIMs and central universities. To create an educational ecosystem which is competent and excellent, why don’t we create thousands of ITIs of national level where the quality comes up?

We have unfortunately done injustice to this sector by setting up a new system which has demolished the traditional ITIs of the country. Today, ITIs have become a neglected kind of institution. But when it comes to long-term training, ITIs are still important. If a Maruti manager has to employ a technician, he will never go to his automobile skill council to get a three months trained worker, he will still go to ITIs.

The centralisation of these skill development institutions should happen. There has to be an assessment system which is controlled by the government. This used to be earlier with DGT (Directorate General of Training). But unfortunately, that has been dismantled, now these sector skill councils have mushroomed. Why NSDC was kept initially under the Finance Ministry was because those who couldn’t afford training were given a loan so that they can go to the industry for employment. But later, it was shifted to Ministry of Skills and the traditional DGT was totally dismantled.

Instead of strengthening the traditional NCVT (National Council of Vocational Training) which used to the traditional system of the country, these skill councils were introduced which have unfortunately not been able to meet the expectations. Whatever objectives were set up for skilling in India could not be met. Industry specific skills will be created as the sector skill councils are being set up by the industry. Unfortunately, these sector skill councils have become a money-making machine for industry associations. For example, a trainer has to go for retraining and assessment every year just because the skill council wants to get a fee out of it. For every certification, a huge sum of money is taken.

Another point I want to make is if the industry has taken the responsibility of formulating a curriculum and training, why don’t they provide employment? Why is it only the responsibility of implementing agency to provide placement? That means the curriculum that they have set up or the assessment they conduct are faulty. We need to make this skill system simpler. Unfortunately, the system created by NSDC are more tilted towards the organised sector. There are many things which we need to address. Only then the skilling can be improved. There should be more discussions with implementing agencies, assessment agencies and the employers. After five years, we reinvent the scheme and think that we will be able to focus on all the problems. That don’t plug the gaps that is there in the existing system. This is not going to work. The Skill Mission to a large extent has failed.

Varun Elembilassery: Should we focus on generalisation of skills or expertise? When we focus on cognitive skills, multi-disciplinary learning and employability, what will be its impact on innovation?

Dr Mantha: Within the skill domain, multidisciplinary will not be looked at in the same sense as we talk about multidisciplinary in a higher education sector. What I meant was that there are today skill programmes that are given by the training centres. The training that is given is at a certain level and in a certain sector. Unfortunately, the industry is so discreet in absorbing somebody trained at level 4 or in the tourism industry, hotel industry, or the automobile industry etc. Those kinds of jobs really don’t exist. Actually, what one requires is to group the skills in the same sector and provide maybe 3-4 skills in order to become employable. There cannot be disparate skill grouping from different sectors. In the same sector, if you can group 3-4 skill sets, then probably that has a larger chance of being employable. That is one point.

The second is, there are several things which Sanjay-ji referred to and they all have a very close connect to some of the questions that you have asked. The implementation has been faulty and that is something that we have been saying for a period of time. I have also interacted with several training providers and the way they train and the kind of difficulties they have. Therefore, there is a certain reimbursement that happens if they are able to place the students. But they are unable to place 60 per cent of the students. This is an inbuilt feature for failure.

What happens is that people tend to make their entire proposal on the 60 per cent base assuming that they can’t place the students. Subsequent to that the entire supply chain works. There is a course correction that is required. There has to be some sort of connect between the skills that are required in the same sector but at different levels. For example, somebody could find a job in the construction sector as a site supervisor having being trained in certain set of skills. But if he were to be trained only in bar bending and he would go out looking for a job, I don’t think that works. That was the idea with which I tried to talk about multidisciplinary.

Brig Jeewan Rajpurohit: Before I ask my question, I would like to quote two aspects. One is that when a student goes to school, college and then to his career, the West talks about college readiness, career readiness and finally job readiness. Kautilya in Arthashastra spoke about asking each student at the age of 11, 16, 21 and 25 as to how he/she would like to progress in respective career. Depending on wherever one wants to deviate from education, if skill is there, he/she gets into the skill. Even to the extent that Kautilya said, women who want to be prostitutes, the level of those prostitutes were defined and they used to be employed. That is how possibly in the welfare state, whether it is economics, defence strategizing, he could place each individual in the slot which is required to be catered to and then creating the correct mass for that slot. Having said these two aspects, my question still remains that skill centres, colleges, our individual homes – are they really geared towards creating an individual who is an asset to the nation or are we creating organisations and then attempting to fit into wherever possible and in the bargain, we say 30 per cent, 40 per cent, 80 per cent success achieved? I would like you to throw some light on the practical aspects of it.

Dr Mantha: I will give you a counter to what you have said. The way the system seems to be operating and the way we are trying to modulate the entire working. When I was the chairman of AICTE, people were constantly questioning as to why permissions were being given to new institutions when there were people who were already unemployed. On the contrary, what was happening was the institutions were coming saying that there are employment opportunities in certain discipline and certain branches of engineering and therefore, they want to expand only in that area. This is based on perception. There is no real data that is available. When we tried to put a stop on this, they went to court. The court asked a very simple question. We said that we want to stop the proliferation because there is a deficit in quality. So, the court said how do you presuppose the deficit of quality in a new institution that comes up? You have a regulatory job, you check the institutions which are there now and maybe close them. But you cannot stop doing that for 2-3 reasons. One is you have the fundamental right 19(1) (g) which says that you can practice any profession that you want. The second is, you are putting in your own money and the land belongs to you. The government doesn’t come in any of these issues, so how do you stop someone from setting up an institution? What was happening was that the institutions on one side were working on perception. They feel that there are jobs in IT, so everyone can get placed. In fact, they were closing down mechanical, civil and starting computer science, IT, just because they perceived that there were employment opportunities. It was never connected to a system that was based on data and metrics.

Same thing is happening in skills. We assume that there is a certain job available somewhere. Or the skill centre feels that there is a certain job available somewhere and they create a business model out of that. There are industry bodies like FICCI, CII, ASSOCHAM; I will ask a very simple question, have they ever given you a single report which actually connects how many engineers you require or how many plumbers you require? You can add 10-20 per cent over that and create and design your entire skilling system to accommodate that. That doesn’t seem to be happening. We are only working on somebody’s perceptions and ideas. Tomorrow if somebody says that constructions supervisors are required, every skilling centre will start doing that. Somewhere, we need a larger plan.

There must be a mapping of what is happening with the industry, what kind of jobs are available. The industry bodies must be made more responsible and they must come out with some kind of figures which can be depended on. In fact, when I asked NASSCOM as to why they can’t reveal their numbers that are of different expertise requirement within the industry, they said that many of the IT industries do not want to reveal that because their business interests will be jeopardised. And they would not want to answer such questions because other fellow in the business would know what kind of job this fellow is up to. If this is the kind of ecosystem we have, we need to really rethink.

Sanjay Ganjoo: That is why I said they should be made more answerable. If they are making money through certification by just stamping the certificate and not even paying the assessor, they are just making money. If they have devised the curriculum and if they are doing the certification, let them provide employment, at least 25 per cent. Otherwise close these shops, let government do it.

Dr Kumar: I do appreciate the good points which Sanjay Ganjoo ji made. But I think this is a world which requires different sections of society to come together. The government is doing its part and there would be a need for different bodies to do their parts too. If I look at FICCI which is responsible for four or five sector skill councils, they are the ones who created them. Therefore, they should write to the government that they should be closed if they don’t believe in them.

Second, I think there is a social issue here. If you look at the nature of business, what is the problem in terms of India is that the surplus of labour. Most of the people in industry as far as possible and for good reasons, their job is to make profit, would want to give as low as possible to the labour. In many cases, it is below the minimum wages for that particular state. We have even done a survey to understand what is the money which an average newcomer gets when he/she joins the industry and what is his/her expectation in life? What we found was interesting. They get about Rs 8500, sometimes as low as Rs 4000 which is far below the minimum wages, almost half of the minimum wages. Then their expectation is Rs 18000 per month. There was a complete mismatch between what a youth is expecting today and what the industry is willing to give. I understand the point of view of the industry. Given the economic realities of India, if they pay Rs 18000, they will go into loss. It is not really practical. They will say that the interest rate is so high, how can we pay so much and still make profit? So, they have a point. What I was trying to say is that there is a responsibility at different levels and each of them is trying their best to get things going.

There is one more important thing. If you look at the big group here, most of us will have drivers and household workers. How many of us are in contractual relationship with them? Everything that the government is trying to do is formalise. They want the people to prosper and its focus is always that. I think what we as individuals can do is to see if we can formalise people who work with us? Or do we want to keep them as non-contracted workers? Partially, it is also social responsibility. It is a cultural issue. If you look at the law of the land, each of us is doing this illegally because the Labour Law requires us to issue them contracts. If you were in a different country, you will follow the rule because somebody will come to your home and hold you accountable for that. I think partially, we have to reflect inwards also. Blaming government for everything is not wise. That is my honest belief. I have been working in government for a long time. I do see a lot of good intention on behalf of the government. But the challenge is heavy. As I said, it is 1.3 billion. Therefore, different parts of the community coming together, appreciating what is right and what is wrong and sorting it out is the right way ahead. I am fully with Sanjay-ji that the skill centres should have 20-30 people from the industry on the board and not one per cent being employed by those industry leaders.

It is very important that we see things in perspective and realise that the government is trying its best. If you look at the first job of the government, it is to bring things into the social agenda. I think it has succeeded well. Today, people talk about skills and they understand its value. That is why we are having this webinar. It is a very good thing. The differences lead to discussion and betterment of our system and better belief system also. So, the agenda setting part is done. It is hardly seven years since we began. If you look at the ministry, we started in 2015 and it is 2022. The education system is ten times older. There at least you will find examples of excellence. Sanjay-ji is right. We now need institutions of excellence. How do we create those? How do we create IIT equivalents to ITIs? How should we think about it? It is time for that and the NEP is fully equipped for that. My own faith that things are moving in the right direction is high. I would never say that we are perfect. We have much to do and we need to move forward for that. I did enjoy this discussion. Thank you for being honest and frank. Thank you so much.

Dr Ratnoo: Thank you everyone. Thank you, Mantha ji and Manish Kumar ji. It was very good to hear your valuable ideas and insights and to have a very fruitful and productive discussion. I am thankful to all of you for giving your time. Thank you so much for joining us today.